Profound racial and ethnic disparities in health and well-being have long been the norm in the United States.

Black and American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) people live fewer years, on average, than white people. They are also more likely to die from treatable conditions; more likely to die during or after pregnancy and to suffer serious pregnancy-related complications; and more likely to lose children in infancy. Black and AIAN people are also at higher risk for many chronic health conditions, from diabetes to hypertension. The COVID-19 pandemic has only made things worse, with average life expectancies for Black, Latinx/Hispanic, and, in all likelihood, AIAN people falling more sharply compared to white people.

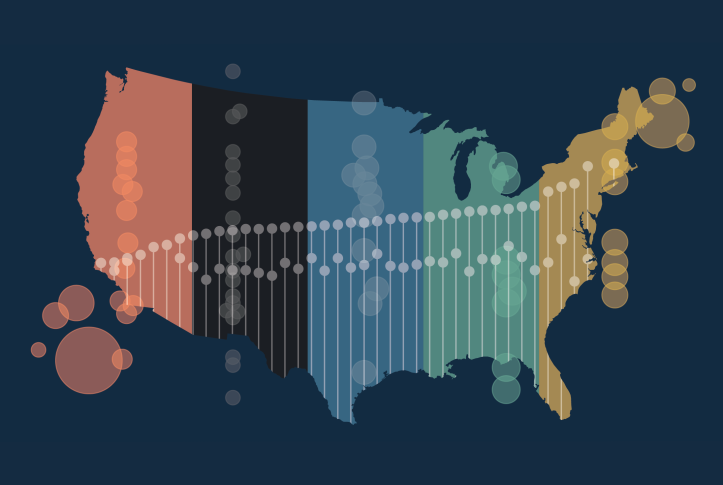

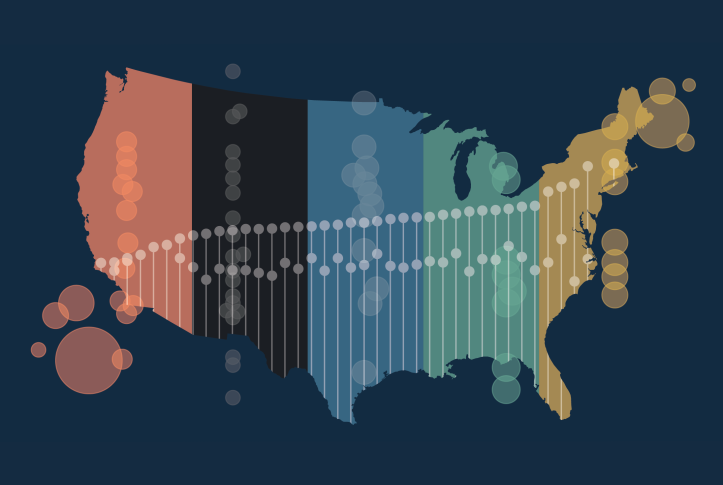

People’s health also varies markedly across and within states, as does access to health services and overall quality of care. Large racial and ethnic health inequities, driven by factors both inside and outside the health care delivery system, are common. In many communities of color, poverty rates are higher than average, residents tend to work in lower-paying industries, and residents are more likely to live in higher-risk environments — all contributors to COVID-19’s disproportionate impact.